"The Old Man wants you to go to the motor pool. Get a vehicle, drive up to

Schloss Glucksburg and fetch Speer. It sounds like he’s playing the

truant again. Bring him back, no excuses. The Grand Admiral doesn’t

care if he’s dying of cancer. Do you think you can do it?”

"Jawohl,” answered Ziggy, jumping to his feet. “I’ll bring him back

immediately.”

"Good,” said Ludde-Neurath. “Try not to start any gun battles.” Ziggy

could see the glint of amusement in the senior officer’s eyes. Had

his time in the doghouse already ended?

The motor pool assigned him a small kubel with exactly one liter of

petrol in the tank. Ten minutes later he was approaching Glucksburg.

In the daylight, uncloaked from darkness and shadow, the schloss

hardly resembled the place where only two nights before they’d

fought a crazed gun battle. Instead what he saw was a slightly

garish, tall white building, not at all fearsome, with narrow windows

and uninteresting proportions.

Driving up to the front gate, he was met by a squad of armed but

dispirited-looking Wehrmacht. Ziggy wondered where they’d been the

night of the battle. Had they absented themselves by prior

arrangement or simply upon seeing Himmler’s men drive up.

The soldiers stepped aside and Ziggy motored slowly through the narrow

forecourt passage. As he passed out of the rear portal and began

driving over the bridge, something up on the battlements caught his

eye. He looked up against the sunlight and saw the outline of two

men juggling. Stopping the car, he held his hand up against his

forehead to shield his eyes from the glare. One of the men was

unmistakably his brother Manni. The other was not so tall, a little heavier and

older, but also surprisingly nimble, like he’d been doing it for

years. It was Speer.

Ziggy drove on across the moat and into the castle courtyard. A sentry

escorted him inside to a small reception room, where a minute later

he was met by a thin young man in a gray suit. “I’m sorry, but

the Reichsminister is busy,” he told Ziggy.

"The Grand Admiral wants Reichsminister Speer to report to the government

building immediately,” said Ziggy.

"I shall give him your message,” said the young man.

"No, he is coming with me,” said Ziggy. “I have orders to bring him to the Grand Admiral.”

The young man led Ziggy into a large parlor which had been converted into

a makeshift typing pool, where a half dozen young women sat

clattering away at typewriters while two others fed paper into a

mimeograph machine. He found a chair and sat down.

A minute later, the door opened and the young man stepped back inside,

followed by a long stream of

men in American uniform who, except for

a few, seemed distinctly unmilitary. And unlike the British up at the

Marineschule, who treated any Germans they encountered with a rancid

prickliness, these men all seemed relaxed and downright jovial.

The secretary pursed his hands together. “Please excuse the disarray, gentlemen,” he said.

"Oh that’s all right,” quipped a tall, beaky man who looked like he could use a haircut.

"Is all this for us?” asked another, pointing at several neat stacks of documents lined up on one of the tables.

"Yes, it is,” said the young man in slightly labored English. “Those are the reports on the electrical industry.”

"Excellent, excellent.”

"I will go up and notify the Minister that you are here. Please excuse me, gentlemen.”

As soon as the young man had closed the door behind him, the Americans

padded around the table mischievously. One of the typists gave them

a disapproving glare.

"Excuse us, ladies,” said one of them.

"Sprechenzee English?” asked another with a sheepish smile. The young woman

glowered back and continued typing.

Then they spotted Ziggy sitting in his chair. “Hello,” one said.

"Hallo,” answered Ziggy.

"Do you, uhh, sprechenzee...”

"Yes, I speak English,” answered Ziggy.

Suddenly they were all interested in him. “Do you work for Speer in some capacity?”

"Howdja get that Iron Cross?”

"Were you in U-Boats? What can you tell us about production of the Type XXIs?”

"Say! Aren’t you Ziggy of the Flying Magical Loerber Brothers? I used to watch you perform at the Blue Star.”

"At that, the secretaries all looked up from their typing. “Ziggy?”

Then one of them pointed at him. “Look! It’s Ziggy! Ziggy!” The

collective gasp that went through them sounded more gut-wrenching to

Ziggy than a torpedo detonating against the hull of a ship.

"Holy Cow, Paul, you’re right, it is him.”

"What are you talking about? Magical who?”

"The Flying Magical Loerber Brothers, Ken. I can’t believe you’ve

never heard of them. Four brothers, identical quadruplets, the

biggest thing in vaudeville, everyone loved them!”

"Paul’s right! These guys are famous. I must have seen them perform a dozen

times at the Blue Star. They were fantastic!”

Then they turned to Ziggy. “I saw you perform at the Admiralspalast,” one said.

"I saw you perform at the Mocambo Club,” said another.

"Ziggy Loerber, Holy Cow!”

The women had stopped typing and were staring at him as if they hadn’t

decided whether it would be improper to get up and flock around a

favorite star who was now a naval officer with the Knight’s Cross

around his neck.

Still seated, Ziggy stared back at them and knew something didn’t add up.

Why were they acting so excited towards him? Surely they knew Manni

was already there with Speer. But maybe they didn’t. So what was he

doing there if they didn’t know about it? He had to be there as a

spy. Why else would he be juggling in plain sight with Speer? Could

he be there to kill Speer? But why?

Ziggy decided he needed to move quickly. He stood up from his chair and

gave a curt bow to the secretaries and the Americans. “Excuse me, but I must go.”

"But Herr Loerber, wait!”

He stepped out of the salon, carefully closing the door behind him.

Speer was coming down the stairs with his secretary. With his eyes

settling briefly on Ziggy, the secretary whispered something to

Speer. Speer nodded noncommittally and then proceeded past Ziggy to

the salon door.

Ziggy stepped in front of the door. “Excuse me, Herr Reichsminister,” he said.

"Yes,” asked Speer, looking directly at Ziggy for an instant before turning

to his secretary with his eyebrows raised slightly in reproach.

Ziggy continued unflustered. “The Grand Admiral has instructed me to

drive you to the Marineschule.”

Speer regarded him bemusedly. “But Captain, don’t you see, I have guests.”

For a moment, Ziggy felt completely intimidated by Speer. He had a

presence that bespoke superiority and wit and honestly acquired

arrogance.

"The Grand Admiral wants you there, immediately,” Ziggy said in the same tone he always gave orders in.

Speer shrugged. “All right,” he said. “Let’s go.”

Ziggy shook his head. “First I must speak with my brother. Where is he?”

I beg your pardon,” said Speer, looking puzzled.

"Manni Loerber,” said Ziggy.

Speer studied Ziggy like he was a buried memory already working its way out

of the ground. “Second staircase on your left,” he said in a

guarded tone.

"Thank you,” said Ziggy and started running up the corridor.

The staircase went up five flights, after which the carpet and white

walls gave way to wood and bare stone. He reached the top landing

and, pushing open a heavy door, stepped outside onto the sun-washed

expanse of battlements. He looked about the different stone walkways

connecting the four towers, but saw no one. He walked over to the

parapet and leaned down from one of the tooth-like gaps to take a

look. Below was the lake and the green fields and the carpet of trees

beyond. Then he felt something cold and hard press against the side

of his neck. “What are you doing here?” asked a man’s soft

voice.

"Manni, it’s me,” said Ziggy.

"Zigmund?”

"Would you get the gun off me?”

(An abbreviated version of this chapter appears in

Germania, first published by Simon & Schuster in 2008, now also available on Kindle

here).

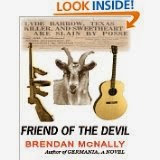

Yes, it's that time of year again! Holiday season. And let's face it, you're about to go out to some busy mall and you're going to shell out your hard-earned Reichsmarks to buy aftershave, ties or a pair of argyle socks, for that special World War II-addict in your life. And why? Especially since you know they'll never use them. The reason, of course, is that you can't stand having to go into a Barnes and Noble or some other bookstore and buy some overpriced and totally lame WWII book, because you have no idea what books they already have.

Yes, it's that time of year again! Holiday season. And let's face it, you're about to go out to some busy mall and you're going to shell out your hard-earned Reichsmarks to buy aftershave, ties or a pair of argyle socks, for that special World War II-addict in your life. And why? Especially since you know they'll never use them. The reason, of course, is that you can't stand having to go into a Barnes and Noble or some other bookstore and buy some overpriced and totally lame WWII book, because you have no idea what books they already have. Buy Germania for your dad or brother, or your boyfriend, or yourself.

Buy Germania for your dad or brother, or your boyfriend, or yourself.